Lawrence

Beitler was sitting on the

front porch of his home in Marion, Indiana,

when someone asked him to tote his 8×10 view

camera to the town square. It was past

midnight on August 7, 1930, and Beitler, 44,

was a professional photographer who mostly

shot portraits of weddings, schoolchildren,

and church groups. That night, he would be

photographing a lynching. He “didn’t even want

to do it,” according to a later interview with

his daughter, “but taking pictures was his

business.”

By

the time Beitler arrived on the square, a

jubilant mob of nearly 15,000 white men,

women, and children had gathered. Earlier that

night, a group of vigilantes had charged the

county jail to seize two black teenagers —

Thomas Shipp, 18, and Abram Smith, 19 — who’d

allegedly raped a young white woman and

murdered her boyfriend. Beitler took one photo

of Shipp’s and Smith’s brutalized bodies

hanging from a tree, the crowd of eager

onlookers before them, and left.

Lynching,

in the American imagination, is considered to

be solely the provenance of Confederate

racism, one of the most prominent examples

being the 1955 murder of

14-year-old Emmett Till in Mississippi. Yet

the most notorious lynching imagery prior to

Till came from Union towns: Duluth,

Minnesota; Cairo,

Illinois; Omaha,

Nebraska —

and Marion, Indiana. It is Beitler’s

photograph, in particular, that has served as

the most glaring visual reminder of the

country’s decades-long spectacle of racism and

public murder. The photo of the lynching of

two Indiana teenagers would never grace the

pages of the local paper. But the image is

everywhere.

It

was Beitler’s photograph that inspired Abel

Meeropol to write his anti-lynching poem

“Strange Fruit” in 1936, which Billie Holiday

would later record and make famous. Just last

month, a decade-old mural

adaptation of

the photograph in Elgin, Illinois, which

features only the faces of the white

participants, came under public scrutiny as

people discovered the image’s origin.

The

photo of the lynching of two Indiana teenagers

would never grace the pages of the local

paper. But the image is everywhere.

I

can’t say exactly when I first encountered the

image. It might have been as an undergrad at

Columbia, in the library of the black

students’ lounge as I thumbed through a copy

of Ralph Ginzburg’s 100

Years of Lynchings.

But my understanding of its significance came

in the late summer of 1996, when a friend and

I visited America’s Black Holocaust Museum

(ABHM) in my hometown of Milwaukee.

When

we entered the main exhibition room, there was

a built-to-scale rendering of Beitler’s photo

made out of wax, including the facsimiles of

Shipp and Smith hanging from the tree. “Did

you know that there was a third boy they tried

to lynch that night?” our museum guide, a tall

but frail older man, asked us, his voice warm

and gravelly. We didn’t. Our guide went on to

explain that there were actually three ropes

strung up on the maple tree in Marion on

August 7, 1930. A third teenager had been

dragged from his jail cell to the courthouse

square. His name was James Cameron and he was

the only known person to have ever survived a

lynching in America.

We

were standing in front of him.

Cameron,

then 82, continued to recount to an audience

of two the details of the night he nearly

died. A self-taught historian and recipient of

an honorary degree from the University of

Wisconsin, Milwaukee, he founded ABHM in the

1980s. Cameron, who died 10 years after I met

him, devoted his life to never letting America

forget what happened to him, resolute in his

belief that his life was spared to educate

black and white Americans of the long, bloody,

violent, and — ever ongoing — legacy of

racism.

I

was astounded. It was one thing to witness the

brutal deaths of these young men. It was

another thing to survive that nightmare and be

staff, curator, historian, executive director,

and living testament to it daily.

How

do you wake up every day and bear witness to

your own nightmare?

James

Herbert Cameron was

born in La Crosse, Wisconsin, in 1914, the

second of three children to James Cameron and

Vera Carter. His family moved south to

Birmingham, Alabama, and lived there until his

parents separated in 1928, after which

Cameron’s mother moved him and his two sisters

to Marion, a modest town of nearly 30,000

where black and white residents attended

integrated schools, yet maintained segregated

social spaces. (Much of Cameron’s biography

and his recollections in this story come from

his memoir, A

Time of Terror.

In

the summer of 1930, Marion, like much of the

country, was experiencing a heat wave that

compounded the effects of the Dust Bowl, and

scores of people were out of work as the

Depression began taking its toll. Cameron,

then 16, spent the afternoon of August 6 with

his buddies, Tommy Shipp and Abe Smith,

pitching horseshoes in a field. It was Smith

who convinced Cameron to join him and Shipp

later that night to “stick up” unsuspecting

couples in a secluded area of town known as

“lovers’ lane.” The three teens drove there,

armed, and attempted to rob Claude Deeter and

Mary Ball, a young white couple. But Cameron

recognized Deeter — he regularly shined

Deeter’s shoes in town and Deeter tipped well.

Cameron,

who had been holding the gun, gave it back to

Smith and ran. He heard shots in the distance.

Shipp and Smith were arrested shortly after

the shooting and allegedly named Cameron as

the shooter. Officer Harley Burden, the only

black officer on the Marion police force,

found Cameron at his mother’s home and took

him into custody.

Once

Cameron arrived at the Grant County Jail in

the early morning hours of August 7, there

were already groups of men waiting as word

spread of the attack. Deeter was dead by early

afternoon, and a police officer hung his

bloody shirt in the window of city hall as a

visible flag. But Deeter’s death wasn’t the

principal outrage that wagged on everyone’s

tongues: His companion, Mary Ball, accused

Shipp, Smith, and Cameron of rape (an

allegation she’d later recant). It was this —

the story of Ball’s alleged assault told over

and over — that incensed the white residents

of Marion and surrounding towns. In his

account of the day, A

Lynching in the Heartland,

Indiana historian James Madison noted that

local phone lines were clogged with callers

discussing the alleged crimes of the three

boys.

For

black residents of Marion, such as Katherine

“Flossie” Bailey and her husband, Dr. Walter

Bailey, it became clear that not only were

Shipp, Smith, and Cameron in danger, but the

town’s entire black community was too. The

Baileys were among Marion’s most prominent

black families. Walter was the only black

physician in town and Flossie was the

president of the state branch of the NAACP. In

the aftermath of the arrests, they made every

effort to rouse authorities to protect Marion

— sending a cable to Gov. Harry Leslie,

calling for the National Guard. They phoned

the county sheriff, Jacob Campbell, several

times demanding that he relocate the three

teenagers, as well as seek additional support.

Campbell rebuffed their calls and offered his

assurances that the boys would be protected.

Marion Mayor Jack Edwards, elected only a year

prior at the tender age of 27, conveniently

left town for “business.” Meanwhile, other

black Marion residents fled to neighboring

Weaver, a mostly black community, to stay with

relatives.

By

9 o’clock on the night of August 7, the mob

had swelled to an estimated 15,000. The

streets around the courthouse were blocked by

crowds and cars. Campbell, who occupied the

residence attached to the jail, moved his

family to another part of town. “The thing I

remember most vividly,” his daughter later

recalled, “was seeing so many people, women,

standing out there in the crowd with little

tiny babies in their arms just hollering, ‘Get

in there and get ’em, get in there and get

’em.’”

Mary

Ball’s father, Hoot, approached the jail

entrance and demanded the keys. “Let us get

the niggers,” he told Campbell. “If this was

your daughter, you would do the same as I am

doing.” From his second-floor cell, Cameron

heard Campbell proclaim, “These are my

prisoners. Go home!” Yet he was not comforted

by the sheriff’s declaration. “Perhaps I

imagined it,” he’d later write in his memoir,

“but I could not detect a note of sincerity in

his voice.”

The

mob surged forward,

some pummeling the jail with sledgehammers

while others forced their way through the

garage. When they breached the ground-floor

walls, they snatched Tommy Shipp first from

his cell. Mary Ball’s sister purportedly

watched from atop a car, encouraging the mob

to wrap a rope around his neck and lynch him.

He was already bruised and beaten when they

strung him up on the maple tree at the corner

of Third and Adams streets outside of the

courthouse, diagonal from the jail. Shipp

struggled to free the rope from his neck. The

mob lowered him, broke both his arms, and

pulled.

“I could see the bloodthirsty

crowd come to life the moment Tommy’s body

was dragged into view.”

Cameron

surveyed the gruesome scene from his cell. “I

could see the bloodthirsty crowd come to life

the moment Tommy’s body was dragged into

view,” he recounted in his memoir. “In a

matter of seconds, Tommy was a bloody mass and

bore no resemblance to any human being. The

mob kept beating him just the same. Even after

the long, thick rope had been placed around

his neck, fists and clubs still mauled him,

and sticks and stones continued to pummel his

body.”

After

the throng returned for Smith, they beat him

with crude weapons, and a man impaled him with

a pipe. Smith was dead before they tied the

noose around his neck. Cameron heard the

gleeful cries once the deed was done. Nauseous

and drenched in cold sweat, he knew what was

next.

“We want Cameron! We want

Cameron!” he heard them chant. When a group

of white men forced their way onto the

second floor, the black men in his cell

block made a fruitless attempt to hide and

protect him. “Impulsively, I acted like I

was going to give myself up when Big John

and another Black man grabbed ahold of me

and held me back,” he wrote. “They had

become too angry to remember their own fear

— if they had any. But they were helpless

and powerless to offer any kind of

resistance to the mob. They stood with me.”

When

the mob threatened to lynch another boy, in

jail with his father for hitching trains from

the South to look for work, the father pointed

to Cameron. “The nightmare I had often heard

about happening to other victims of a mob now

became my reality,” Cameron wrote. “Brutally

faced with death, I understood, fully, what it

meant to be a black person in the United

States of America.”

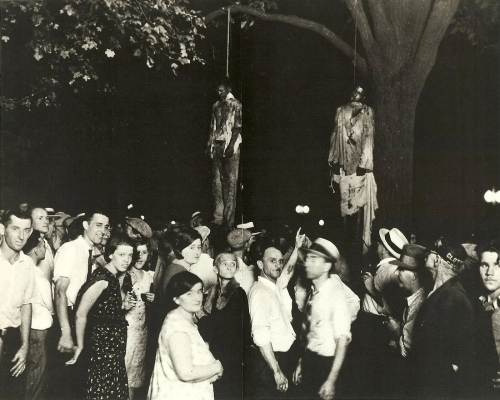

Beitler’s

photograph of the August 7,

1930,

lynching in Marion. Lawrence

Beitler

- Indiana Historical Society

Cameron

was punched and

kicked as he was dragged from the jail’s second

floor to the maple tree. “I didn’t rape anyone!”

he howled over the din of the crowd. Half

conscious, he felt the noose being wrapped

around his neck. “The rope was handled so

roughly it caused a rope burn,” he wrote. “For a

moment I blacked out. I recovered in a moment

though, as they began shoving and knocking me

closer to the tree under the limbs weighed down

with the stripped bodies of Tommy and Abe.”

Yet,

just as Cameron prepared for the end, someone

spoke up. In Cameron’s retelling, a voice “rose

above the deafening roar of the mob,” speaking

“sharp and crisp, like bells ringing out on a

clear, cold winter day.” The voice — “feminine”

and “sweet” — delivered a simple instruction:

“Take this boy back. He had nothing to do with

any raping or killing.”

A

swift silence followed. “No one moved or spoke a

word,” Cameron wrote. “I stood there in the

midst of thousands of people, and as I looked at

the mob round me I thought I was in a room, a

large room where a photographer had strips of

film negatives hanging from the walls to dry. I

couldn’t tell whether the images on the film

were white or black, they were simply mobsters

captured on film surrounding me everywhere I

looked.”

The

identity of whoever intervened — or whether

anyone intervened at all — remains a mystery to

this day. Cameron believed it could only have

been the voice of God, though according to later

accounts, some never even heard the “angelic”

voice he described in his memoir. According to

Madison, most of those who did claim to hear it

said it was a man’s voice, with some believing

it was Mary Ball’s uncle.

“I suddenly

found myself standing

alone, under the death tree

—

mystified!”

Regardless,

after what Cameron called a “brief eternity,”

“the roomful of negatives disappeared.” “I found

myself looking into the faces of people who had

been flat images only a moment ago,” he wrote.

“I could feel the hands that had unmercifully

beaten me remove the rope from around my neck. I

suddenly found myself standing alone, under the

death tree — mystified!”

As

the crowd cleared a path between the tree and

the jail, Cameron limped back, uttering a prayer

with each step. No one laid a hand on him. When

Cameron reached the steps of the jail, Sheriff

Campbell took him by the arm and led him to a

police car with armed officers who immediately

escorted him to a jail in Huntington, nearly 30

miles north of Marion. The following day,

Cameron was moved 30 miles south of Marion to

Anderson, Indiana, and the National Guard

arrived in Marion, per Gov. Leslie’s orders.

It

would be after midnight that Lawrence Beitler

would make his way to the courthouse square with

his view camera and flash, in the thick and

humid dark. Sheriff Campbell cut Shipp’s and

Smith’s bodies down the next morning. Some

Marion residents reportedly collected trophies

from the murders: scraps of Smith’s and Shipp’s

clothing, pieces of bark from the maple tree,

and pieces of the lynching rope itself, an item

that was highly coveted. Beitler stayed up for

10 days and nights to meet the demand for prints

of his photograph, which he sold for 50 cents

each. According to a 1988 Marion

Chronicle-Tribune interview

with his daughter, Betty, “It wasn’t unusual for

one person to order a thousand at a time.”

From

1882 to 1968, 4,743

Americans —

3,446 of whom were black — were lynched, their

deaths fueled by fears over miscegenation and

perceived threats to white economic

dominance. While the majority of lynchings

did take place in the South, 128 black Americans

were killed by Northern lynch mobs between 1880

and 1930. Between 1889 to 1930, 21 black people

were lynched in Indiana alone.

Motivating

many of these lynchings — and, in several cases,

preventing law enforcement from stopping them —

was the influence of the Ku Klux Klan. According

to A

Lynching in the Heartland,

in 1920s Indiana, white, native-born Hoosiers

joined the Klan in droves, feeling increasingly

threatened by black migrants heading north from

southern states. By 1925, membership peaked at

250,000 and encompassed more than 30% of the

state’s white male population, allegedly

including then-Gov. Edward L. Jackson and other

high-ranking officials in the state.

That

all changed, however, in 1925, when Grand Dragon

D.C. Stephenson was convicted for the rape and

murder of an Indianapolis student. His highly

publicized trial, paired with his implication in

widespread state political corruption, quickly

depleted membership. By 1930, the Indiana Klan

ceased to be a public force, but the vestiges of

its influence still pervaded local politics.

While the Klan never claimed responsibility for

the lynching of Shipp and Smith, it’s highly

probable that former members and sympathizers

participated.

From 1882 to 1968, 4,743 Americans

were lynched.

Indiana

state law already required law enforcement to

protect prisoners from lynchings, and officers

could have faced removal from office upon

failure to do so. However, not once did Campbell

fire a shot in an attempt to disperse the crowd.

“If a shot had been fired, three or four hundred

persons, including women and children,

undoubtedly would have been killed,” Campbell

later told the Indianapolis

Times.

“One shot would have been the signal for

slaughter.”

“The sheriff and police

completely laid down,” Flossie Bailey wrote in

an August 8 letter to Walter White, then

executive secretary of the NAACP, “after

assuring the Executive Board [of the NAACP]

that every effort would be made to avert the

tragedy.” Bailey requested White’s assistance

to pressure state officials to investigate and

send protection for the black residents of

Marion. White arrived in Marion a week later

to conduct his own investigation in tandem

with the state’s inquest, interviewing

witnesses to try to determine the identity of

leaders of the lynch mob. Though Beitler’s

photograph circulated widely, no one came

forward to identify people to authorities.

Billy

Connors, the manager of a theater near the

courthouse, was one of the few white residents

of Marion to rebuke local law enforcement’s

actions on the record. “I am going to tell you,

that if what I understand is right — and I have

heard a lot of talk — they knew something was

going to happen,” he told state investigators.

“We are supposed to have a police force here

ample to protect the city; why they were even

allowed to gather I can’t understand.”

Ultimately,

two trials were held in attempt to prosecute the

ringleaders of the mob. Eight men were charged

as inciters, in addition to Sheriff Campbell,

who was charged with failure to protect Shipp,

Smith, and Cameron. However, by the end of March

1931, juries acquitted two of the alleged

inciters and the state dropped its charges

against Campbell and the other men for lack of

evidence. Hoot Ball was never charged.

Cameron,

having just survived his own lynching, faced a

different fate. Though Mary Ball recanted her

rape accusation, he was still charged as an

accessory to Deeter’s murder. Bailey secured

Cameron two highly respected black lawyers from

Indianapolis, who successfully filed a change of

venue for his trial, moving it from Marion to

Anderson, where Cameron had remained in jail

since the day after the lynching. In July 1931,

11 months after the lynching, an all-white male

jury in Anderson found him guilty of accessory

before the fact to voluntary manslaughter. He

was sentenced to up to 21 years in prison.

Though he was eligible for parole after two

years, he encountered delays from the parole

board. One of the members, a rumored Klan

member, was later discovered to have written

letters protesting Cameron’s release.

When

Cameron was released in 1935, his mother and

sisters stood outside the penitentiary to greet

him. Now 21, he was a free man, resolved “to

pick up the loose threads of [his] life, weave

them into something beautiful, worthwhile and

God-like.”

Virgil

Cameron has the

same kind yet intense eyes as his father. We

met last August at a coffee shop on

Milwaukee’s East Side, a short walk from the

Milwaukee River. At 74, he is a veteran of the

Marine Corps and proudly sported a USMC

snapback honoring his years of service in the

1960s. He was discharged in 1967 to help care

for his father, who, decades after the near

lynching, faced periodic health problems. As

treasurer of the board of America’s Black

Holocaust Museum, Virgil has been the main

family member to continue his father’s work of

educating Americans on the original sin of

slavery and violence against black bodies.

His

passion for history became striking as he told

me little-known facts about the black life in

Wisconsin — like that Milton, 70 miles

southwest of Milwaukee, is home to an underground

railroad site called

the Milton House. “You go downstairs and

there’s a tunnel. You couldn’t stand up, you

had to crawl,” he said. “It’s amazing and it’s

here in Wisconsin.”

Virgil,

Cameron’s third-oldest child, was born in 1942

in Detroit, where Cameron moved following his

release from prison in 1935. Two years later,

Cameron married Virginia Hamilton, a nurse,

with whom he had five children: Virgil, three

other sons, and one daughter. Shortly after

Virgil was born, Cameron moved his young

family back to Anderson, Indiana, the very

same town where he was convicted, to be closer

to his sisters and ailing mother. Now an adult

and a father, Cameron cobbled together jobs,

working for a time for the manufacturer Delco

Remy and opening a shoe shine and convenience

store in downtown Anderson in order to support

his family.

While

Anderson was socially segregated, Cameron’s

family seemed to be exempt from adhering to

those norms. Virgil will never forget the time

his mother and siblings went to the local

movie theater and sat in the orchestra, rather

than the segregated balcony where other black

people would sit. When a white usher tried to

force them to move, his mother refused, until

a white manager ultimately intervened. ‘Those

are the Camerons,” Virgil recalled him telling

the usher. “Leave them alone.” Cameron and his

wife would go on to challenge the segregation

policies of the theater, which eventually

integrated rather than risking lawsuits.

Cameron

and Virginia became prominent members of

Anderson’s black community in other ways, as

well. Cameron served as president of the NAACP

chapter in Madison County, where Anderson is

located, and eventually founded four other

chapters in the state. In 1942, Indiana Gov.

Henry F. Stricker appointed Cameron as the

state director of civil liberties, a position

in which he investigated civil rights abuses

and violations of equal accommodations law.

Yet, according to Virgil, Cameron’s commitment

to civil rights work in Indiana was met with

lukewarm support from other black communities

in the state, who worried his activism would

create “trouble” for them. It also rankled

some white people.

“I know he was getting

threats, but we weren’t really aware of it

until we got older,” Virgil said. “There was

one day when a bunch of cars that pulled in

front of the house and dad grabbed his

rifle, and we went out with him. They were

exchanging words and then the men pulled

off.”

Eventually,

Cameron had faced enough threats, and he

decided to move his family. He chose Milwaukee

after an NAACP speaking engagement landed him

there in 1950. At the time, the city was

receiving a great influx of black Americans,

who relocated from Southern towns and cities

or, as in Cameron’s case, Northern ones that

practiced de facto segregation. The city’s

economy, teeming with blue-collar work and

nice homes, seemed to hold ample opportunity

for families like Cameron’s to live the

promise of the American dream.

And

yet, Milwaukee — like all of America — was

still unable to escape the vestiges of white

supremacy. “It was a good environment, but if

you were black, you were programmed to go to

certain areas,” Virgil said. Cameron’s family

lived in Bronzeville, the heart of

the black community in northeast Milwaukee,

which bustled with black-owned businesses,

restaurants, and theaters. Virginia became a

licensed practical nurse, while Cameron became

a facilities manager at one of the city’s

large malls. Ever entrepreneurial, he also

moonlighted with his own carpet-cleaning

business, which Virginia helped manage.

Together, they built up savings and provided a

modest, middle-class life for their

children.“[They] had us all involved in music,

sports,” Virgil told me. “He always seemed to

want us to expand our horizons.”

Still,

Cameron’s activism didn’t wane once he

relocated to Milwaukee. An autodidact, he

amassed a collection of some 15,000 books over

the years, which supplemented his frequent

trips to the Library of Congress. Cameron

obsessively wrote and read, piecing together

black American history, studying the origins

of the transatlantic slave trade, the Civil

War, and the Klan. He was vocal about racial

discrimination wherever it manifested, writing

columns for the local black papers, the Milwaukee

Courier and

the Milwaukee

Star, as

well as searing letters to the editor of

the Milwaukee

Journal and Milwaukee

Sentinel.

“Everybody was expecting to see his letter to

the editor every week,” Virgil said.

Cameron

also dedicated himself to a project he had

begun while he was still a teenager serving

his sentence at the Indiana State Reformatory:

writing a book about the night he was almost

lynched. “He was constantly talking about this

book, this manuscript,” Virgil told me.

Cameron would spend hours in the basement

writing, provoking the curiosity of his young

son. “I finally asked him one day, ‘Dad, why

are you always typing? What are you doing?’”

Virgil recalled. “He said, ‘I’ll let you read

it, son, when you are older.’”

Virgil

was 12 when Cameron first let him read an

early draft of the book chronicling his near

murder. At the time, Virgil still hadn’t fully

grasped that the boy in the book was his own

father. He thought it was someone else’s

story, possibly a work of fiction. He was in

high school when he finally realized that it

was Cameron who was spared from one of the

most infamous lynchings in American history.

“I felt that he was one … lucky person,”

Virgil said. “There was an intervention that

allowed him to live.”

It

would be a 1979 church

trip to Israel that would seed Cameron’s idea

to create a museum centered on the history of

slavery in the United States and its evolution

into a racialized caste system accompanied by

violence and terror. Upon visiting Yad Vashem,

it struck Cameron that the horrors endured by

descendants of African slaves in the Americas

shared some similarities to the Holocaust.

“It shook me up something

awful,” Cameron told journalist Cynthia Carr

in 1993. (Carr

later wrote a book confronting

the possibility that one of the onlookers in

Beitler’s photo was her own grandfather.) “I

said to my wife, ‘Honey, we need a museum like

that in America to show what happened to us

black folks and the freedom-loving white

people who’ve been trying to help us.’” He

left with a vision and renewed purpose for why

his own life was spared; he had survived to

remember, to educate the nation.

For

years, he sent his book manuscript to

publishers, but no publisher seemed interested

in publishing a first person account of a

lynch mob survivor. (Cameron later told Carr

that he rewrote the manuscript about “a

hundred more times” and collected early 300

rejection letters.) In April 1980, Ebony published an

excerpt of his memoir and dispatched a

photographer who returned to Marion with him,

documenting his visit. However, national

exposure to his story still did not garner a

willing publisher. Undeterred, Cameron took a

second mortgage and self-published A

Time of Terror in

1982. He printed 4,000 copies and sold them

out of his trunk of his car at speaking

engagements.

Cameron

also self-published pamphlets — over 30 total

— in which he drew upon his research and

experiences to illuminate various cornerstones

of white supremacy. In one from 1986 titled

“Police Community Relations Among Blacks in

Milwaukee, Wisconsin,” Cameron protested many

of the same issues being challenged today by

the Black Lives Matter movement. “[The police]

have been enemies of us black people since in

their organization in the early 19th Century,”

Cameron wrote. “They can do nothing to alarm

or silence me beyond murdering me. Even at

that, they may rest assured that I protest it

— even in the grave. I have been initiated

since my time of terror at the age of 16. I am

72 years old now and destined, like all other

nonwhites, to experience a time of terror to

the grave.”

Cameron’s

resolve to build a museum to commemorate and

reconcile America’s dark history intensified

and by the late 1980s, he was able to secure —

rent-free — a modest storefront on Atkinson

Avenue, in a predominantly black neighborhood

on Milwaukee’s north side. The doors of

America’s Black Holocaust Museum opened ceremoniously

on a Sunday in 1988: June 19, known as

Juneteenth, commemorating the day in 1865 when

Southern slaves in Texas were notified of

their emancipation by executive order. Filled

with books and artifacts Cameron had collected

over the years in his basement, it was a

monument to the legacy of lynching in the

United States.

The

location, however, was temporary, and as

interest piqued within the community and more

people came to visit, Cameron searched for a

larger space to accommodate his vision for the

museum. In 1992 — the year before Indiana Gov.

Evan Bayh formally pardoned Cameron for his

1931 conviction — Cameron moved the museum to

the old Braggs Boxing Gym, on Fourth Street

and North Avenue in Bronzeville, which he

acquired from the city of Milwaukee for $1.

With the help of local leaders, Cameron was

introduced to local Jewish philanthropist Dan

Bader of the Bader Foundation. Though

Cameron’s use of the term “holocaust” had

drawn criticism from some Milwaukee Jews,

Bader was struck by Cameron’s knowledge of the

Shoah and the connections he drew between the

persecution of Jews and the descendants of

African peoples in America. According to

Virgil, he wrote a check for $50,000 on the

spot. (When asked about objections to the name

in 2002, Cameron told the Chicago

Reader that

“[American] Indians also needed a holocaust

museum, and that ended any objections they

had.”)

The

donation was crucial for beginning renovations

to the old boxing building, where Cameron had

already relocated the museum after some hasty,

self-funded repairs. It also legitimized the

project to additional foundation and grant

support. Cameron’s vision for the museum

wasn’t restricted to elucidating the horrors

of lynchings. Rather, as with his pamphlets,

he sought to educate Americans on the entire

history of black people in America, connecting

the legacy of slavery as the antecedent to

cruel indignities endured by the children of

the African diaspora. By the early 2000s, the

museum received around 25,000 visitors a year.

Cameron displayed objects he collected over

the years, which included paraphernalia from

lynchings, postcards, photographs from the Jim

Crow era, newspaper clippings that depicted

black Americans, caricaturized miniatures, and

the wax installation of Beitler’s photograph.

In 1999, he also expanded the facility to host

the traveling exhibition of the wreckage of

the slave ship Henrietta

Marie.

However, it was always Cameron himself who was

the biggest

draw.

“We need a museum like that

in America to show what happened to us black

folks and the freedom-loving white people

who’ve been trying to help us.”

Fran

Kaplan met Cameron on an ordinary day in 1999.

The granddaughter of Russian Jewish

immigrants, she was born 70 miles away from

Marion in Lafayette and had vague memories of

hearing about lynching growing up. Cameron

guided Kaplan and her son, who was visiting

from out of town, through the museum’s

exhibits and finally to a seated area to

screen the 1995 BBC documentary Unforgiven:

Legacy of a Lynching,

which retold the story of the night of August

7. In one scene, William Deeter, Claude

Deeter’s brother, tearfully embraced Cameron

at a Marion church; it was the first time the

two ever met. Both men exchanged words of

forgiveness and faith. When the film ended,

Kaplan recalled, Cameron came out to sit with

them and talk. “I was just silent,” Kaplan

remembered. “[I] couldn’t connect with him

because I was so awed.”

Patrick

Sims was a graduate student in theater at the

University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, when he

first visited the museum in 1997. Now a vice

provost for diversity at the University of

Wisconsin, Madison, he recalled that he saw in

Cameron’s story parallels between his own

encounters with police officers. “That could

have been me. That could have been my

grandfather,” he said. His thesis, a

one-person play

based on Cameron’s life called 10

Perfect: A Lynching Survivor’s Story,

intentionally concluded with a reconstruction

of Beitler’s photograph. In performances, Sims

occupied the spot where 16-year-old Cameron

would have been lynched.

The

project created space to share stories

otherwise hidden. Sims learned that his own

grandmother had aided a black man fleeing an

angry mob of white men in rural Missouri. “Why

are we not sharing these experiences?” he

asked, noting how trauma can be

unintentionally passed down between

generations. “Why aren’t we talking about

these things?”

For

some, however, there was a reticence to enter

ABHM’s doors. Lucas Johnson, 32, a lifelong

Milwaukee resident, told me that he “always

wanted to go, just never got around to it.”

Members of my own family have remarked about

making a plan to visit but never did. I too

shared some of this reticence. I supported the

museum’s existence in spirit, but dreaded the

work of confronting America’s ugly history of

violence toward black people.

When

I finally entered those doors, unaware that my

August 1996 visit fell so close to the

anniversary of Cameron’s near murder, I had no

idea what to expect. I don’t remember most of

the conversation. I do remember meeting a

powerful and reserved spirit who showed me the

rope from the lynching tree and other

artifacts of racial bigotry. I didn’t want to

know any of it, but I understood that I needed to.

I also felt psychic pain. I also felt

gratitude. In a world that challenges the

forward assertion of black life, I thought

over and over, Thank

god he lived. Thank

god. Thank god.

In

2005, more than 105 years

after federal anti-lynching legislation was

first introduced to Congress, former Louisiana

Sen. Mary Landrieu sponsored a resolution

to formally

apologize for

the Senate’s failure to pass anti-lynching

laws that would have brought the men

responsible for the deaths of Smith, Shipp,

Till, and so many others to justice. While the

House of Representatives passed several bills

to address the epidemic of lynching from the

1930s and 1940s, these bills died on the

Senate floor or faced filibuster from Southern

Democrats. “There may be no other injustice in

American history for which the Senate so

uniquely bears responsibility,” Landrieu said

before the vote.

Cameron,

then 91 and using a wheelchair, was the only

living representative who could attend on

behalf of the nation’s 5,000 known lynching

victims. When he entered the press room, he

was greeted by 100 photographers and

reporters, and thunderous applause. He recalled how,

after he was taken back to the jail in Marion,

Sheriff Campbell told him, “I’m going to get

you out of here for safekeeping” — only to

learn later that Campbell himself was a member

of the Ku Klux Klan. “I was saved,” Cameron

said, “by a miracle.”

“My father had that strength.

That he could forgive the thing that people

tried to do to him.”

“It was amazing for him,”

Virgil said. “He thought it was the final

recognition for what slavery was. It was the

apology he was looking for that America

should have apologized long ago.” Virgil’s

voice broke a bit. “My father had that

strength. That he could forgive the thing

that people tried to do to him.”

Cameron

died a year later at the age of 92 after

living with lymphoma for five years. The

devout Catholic’s funeral was held at

Milwaukee’s Cathedral of St. John, with

hundreds in attendance, including current

Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker and Rep. Gwen

Moore. His wife, Virginia, died in 2010 at the

age of 92; he is survived by three of his

children and 18 grandchildren and

great-grandchildren.

For

two years following Cameron’s death, America’s

Black Holocaust Museum remained open, with a

modest staff of five and as many as ten to

fifteen volunteer guides — known as “griots” —

who hosted group and school visits. However,

it operated on a shoestring budget and was

eventually forced

to close its

doors in 2008, when the recession exacerbated

its financial struggles.

I

wonder now, with each anniversary of his near

murder, how did Cameron stomach it? How, with

each group of visitors, was he always willing

to relive his trauma? Cameron’s commitment to

educate the American public, including black

people and “freedom-loving whites,” as he

would say, of the terror of racial violence

required strength and unyielding resolve that

I’m not sure any one of us could ever know.

“It’s amazing that over

the years that people have written plays about

lynching, people have written poetry, people

have done visual art … for one thing, you

can’t get too much more dramatic than this,”

Fran Kaplan told me in her home office in

Milwaukee last August, as her finger landed on

the folds of a book opened to a photo of a

lynching from Texas in 1920. “What is the

psychology of committing these kinds of

murders?”

Kaplan’s

initial meeting with Cameron in 1999 would go

on to have a profound impact on her. At 69,

she is now virtual museum coordinator for

ABHM, which continues

to live online,

receiving approximately 700,000 visitors

annually from 200 countries and hosting public

events like talks, screenings, and intergroup

dialogues on anti-racism.

An

all-volunteer operation, it centers itself

around four principles: remembrance,

resistance, redemption, and reconciliation.

In

2015, Kaplan was contacted by a white woman

whose friend was lynched in her home in

Mississippi during the 1960s, a killing that

she felt responsible for. She had tried

reaching out to the victim’s family, but they

wanted nothing to do with her. Kaplan

encouraged the woman to look into Coming to

the Table, an organization that

brings together descendants of lynching

perpetrators and victims to begin the work of

reconciliation.

For

Kaplan, the encounter only underscored the

vision behind her work today: to collect and

tell the stories of lynching victims. “My

perspective, as a white person in this

setting, is to help white people understand

the tremendous jigsaw puzzle that is racism in

America,” Kaplan said. “So they can see the

picture, so that they understand the picture,

so that they can dismantle that picture.”

The

stories ABHM hopes to collect are not only of

how lynching victims died but also of the

lives they led. So often, the story of

lynching is the retelling of what led to

somebody’s death and, for the families left

behind, the shame and fear of the aftermath.

“It goes to the whole sense of Black Lives

Matter,” said Reggie Jackson, chair of ABHM’s

seven-person board. “[The] lives of the people

who were lynched, their lives didn’t matter —

so there’s no reason to mention anything about

them other than the act they committed that

led to their lynching. The newspapers were

like, ‘Who really cares who they were?’”

Jackson

grew up near Money, Mississippi, the town

where Emmett Till was murdered. “For years, I

just wanted to go there,” Jackson said. “And

my family was like, ‘You don’t want to go

asking questions about it.’” Jackson, 50,

visited ABHM in the 1990s after moving back to

Milwaukee from California when he completed

his service in the Navy. Cameron was alone and

gave Jackson a tour, and Jackson bought copies

of pamphlets and his book. Before Jackson

left, Cameron told Jackson his story and why

he started the museum. The two men talked for

over three hours. “I told myself, I

have to come back and help this man,”

Jackson said. He returned to volunteer at ABHM

in 2001 and eventually grew close to the

Camerons, visiting the elderly couple often in

their home.

In

Kaplan’s eyes, Jackson is the protégé of

Cameron. “I wanted to follow in his

footsteps,” Jackson said. He currently works

as a special-education teacher for a charter

school, and in his free time, dedicates his

energies to ABHM.

Jackson,

along with Kaplan, Virgil, and core members of

the board, are working with a local real

estate developer to reopen ABHM at its former

location on North Avenue in Bronzeville,

though the neighborhood is also struggling to

return to its halcyon days. Like most former

urban centers that served the black community,

it experienced rapid economic decline, a

victim of “urban renewal” efforts that led to

the dispersal of black communities and

businesses in the area. In May, Maures

Development was awarded tax credits to

facilitate the construction of a low-income

apartment complex in Bronzeville, the ground

floor of which is anticipated

to provide space

for the museum. “I hope it reopens,” my aunt

told me recently. “To see an actual piece of

history … real things that were used to keep

our people captive. And divided. It would be a

good thing for Milwaukee to have back.”

Museums

educate a class of citizens in the hopes that

presenting the narratives of their nation will

shape identity and fidelity, pass the story

forward, and, perhaps, correct past wrongs. In

the act of remembering, they can serve to

remind a people to do better, be better.

Museums are not always mausoleums to

greatness; they can be an instructional look

at the fullness of humanity, so we never

forget what monsters we can become and

endeavor to resist it. If we forget, we

repeat.

In

1998, three white men tied 49-year-old James

Byrd to the back of a pickup truck and dragged

him to death. In 2011, a group of Mississippi

teens beat

and ran over 48-year-old

Craig Anderson “for fun.” In 2014, the death

of 17-year-old Lennon Lacy led

the Justice Department to open an inquiry to

determine if his death was a lynching in North

Carolina. Nooses proliferate on college

campuses; perpetrators feign ignorance of its

meaning. Last year, a Florida graphic design

company featured a

noose dangling

from a tree as part of an ad campaign for

Photoshop tools. And just a month after that,

in Marion, the boss of a firefighter tossed a

noose into his black employee’s hands. The

employee is married to a distant relative of

Abram Smith.

If

we forget, we repeat.

Yet

perhaps the moment is right for Marion to

again properly revisit and memorialize its

lowest moment. In Glendora, Mississippi,

there’s now a museum honoring

Emmett Till’s life and educating the public

about his murder. Duluth, Minnesota, where

three black circus workers were lynched by a

mob of an estimated 10,000 in 1920, dedicated

a memorial to

the men in 2003. The recent

opening of

the Whitney Plantation in Louisiana and

the forthcoming National

Black American Heritage Museum at the

Smithsonian Institute also seem to point

toward a public readiness to confront the sins

of the nation’s past, even as they persist in

our present.

And

yet, Marion is a place of selective memory. A

few people have contacted Kaplan proposing to

place a memorial there or to relocate ABHM in

the town, but it has simply remained talk.

Occasional visitors to the Marion Public

Library and Grant County Museum come asking

questions. Last August, I was one of them,

when I visited on the 85th anniversary of the

murders of Tommy Shipp and Abram Smith.

Outside the genealogy room in the library,

where some records of the lynching are housed,

there was a modest exhibit of the history of

the county. A dusty photo and display of James

Dean, who was born in Marion, was showcased.

Jim Davis, the illustrator who created

the Garfield comic

strip, also held a place of honor. That week,

a small exhibit celebrating the heritage of

notable black citizens of Marion, including

Flossie Bailey, was also displayed. There was

no mention of Cameron anywhere.

Perhaps

Marion believes it can forget its greatest

tragedy now that the only survivor and witness

to the crime died 10 years ago. Marion today

has endured a fate not dissimilar from many

Rustbelt cities. Its population of

approximately 30,000 has remained steady, but

it bears the scars of economic depression.

Foreclosed homes and empty lots stretch for

blocks.

The

grounds around the courthouse are still

manicured and preserved. They are home to a

boulder with a plaque honoring Martin Boots,

the first white man to set foot in Marion, who

later founded the county. The intersection of

Third and Adams streets — where Smith and

Shipp were lynched — is now a memorial to

Grant County residents who died in the Vietnam

War.

When

I reached the intersection, I took out my

camera. I had taken great care, making sure to

charge the battery of my fancy SLR.

Mysteriously, it didn’t work. The once-charged

battery was dead. Fate or coincidence would

not let me mark the occasion.

A

week later, when I met with Virgil in

Milwaukee, I told him about my camera’s

malfunction, to which he responded with a

knowing look. “You know the tree died, right?”

he said.

Virgil

continued to recall a family visit to Marion

for an event for his father. “The impression

that you get is that Marion … the state that

it’s in, it has not progressed,” he said.

“It’s got that stigma and I think that

lynching has a lot to do with it.” More people

filled the café patio where we sat, their

chatter bouncing off the canopy while wind

rustled the leaves of trees nearby. Milwaukee

weather, fickle as ever, brought a chill to

the late August heat.

“Marion died because of that

incident. It’s just like something is

hovering over that city.”

This

commentary is also posted in BuzzFeed

Collections.

|

|